As Persian language, literature and culture spread far beyond Iran to regions such as India, Central Asia and Anatolia, they played a crucial role in the formation of a Perso-Islamic civilisation that has been termed the ‘Persianate Cosmopolis’, the vast area that ultimately stretched from the Balkans to the eastern borders of India, and culturally, had an even broader impact.

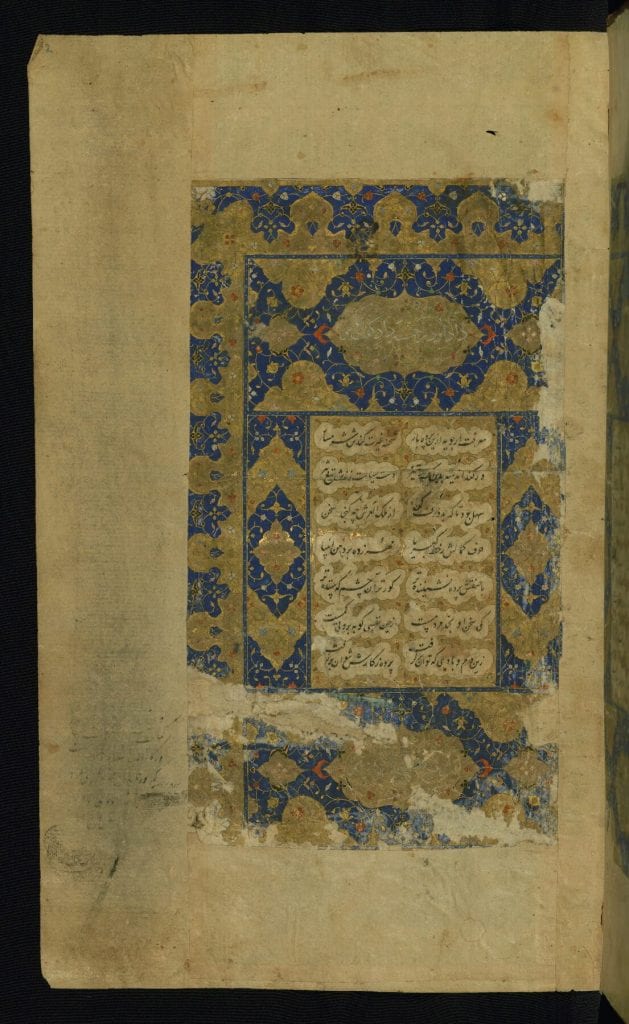

Although there is an awareness among scholars of the crucial role played by Persian language and culture in these areas, propagated through literature, such as epics, in particular the Shahnama, poetry, histories and also art, especially painting, they have rarely been investigated more than superficially, especially in the medieval period. Works by Persian-language writers active outside of Iran often remain unpublished even today, including some major historical sources such as Mu’ali’s Persian verse history of the early Ottomans and philosophical works such as the writings of Sadr al-Din Qunawi, while even well-known figures such as the Indian Persian language poet Amir Khusraw remain comparatively neglected and their works inadequately published.

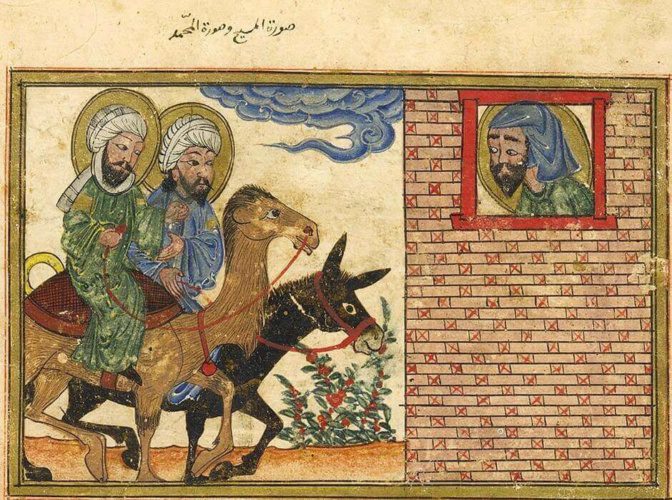

Instead, to date scholarship has largely concentrated on questions of Islamisation and conversion as means by which distant areas of the dar al-Islam were acculturated. Yet although Persian culture often spread in parallel to Islam, it was a distinct process, able to attract those who had no intention of converting, as we can see in the construction of a so-called ‘Persian’ room in the eleventh-century Byzantine palace in Constantinople, and also one with distinct political implications, as indicated by the adoption of pre-Islamic regnal names such as Kayqubad and Kaykhusraw in the courts of Anatolia and India. However, we lack an understanding of why Persianate culture was appreciated by such elites, how it was transmitted, to what extent it was actually seen as distinctively ‘Persian’ and whether this ‘Persianness’ changed over time.

The research programme will encourage scholarly interaction through a major conference that will address such questions, along with considering the means of transmission of Persian culture and the role of migrant Iranians in this, the reason for its adoption and its appeal to non-Iranian elites and others, its interaction with other cultural traditions, whether Islamic, Hindu or Christian, in comparative perspective. Workshop participants would be encouraged to draw on evidence from a variety of disciplines – language, literature, art history and history – to provide a comparative perspective. By drawing together research from a wide variety of different disciplines, the workshops will shed light on aspects of the formation of Perso-Islamic civilisation and the influence of the pre-Islamic Iranian past.

As Persian language, literature and culture spread far beyond Iran to regions such as India, Central Asia and Anatolia, they played a crucial role in the formation of a Perso-Islamic civilisation that has been termed the ‘Persianate Cosmopolis’, the vast area that ultimately stretched from the Balkans to the eastern borders of India, and culturally, had an even broader impact.

Although there is an awareness among scholars of the crucial role played by Persian language and culture in these areas, propagated through literature, such as epics, in particular the Shahnama, poetry, histories and also art, especially painting, they have rarely been investigated more than superficially, especially in the medieval period. Works by Persian-language writers active outside of Iran often remain unpublished even today, including some major historical sources such as Mu’ali’s Persian verse history of the early Ottomans and philosophical works such as the writings of Sadr al-Din Qunawi, while even well-known figures such as the Indian Persian language poet Amir Khusraw remain comparatively neglected and their works inadequately published.

Instead, to date scholarship has largely concentrated on questions of Islamisation and conversion as means by which distant areas of the dar al-Islam were acculturated. Yet although Persian culture often spread in parallel to Islam, it was a distinct process, able to attract those who had no intention of converting, as we can see in the construction of a so-called ‘Persian’ room in the eleventh-century Byzantine palace in Constantinople, and also one with distinct political implications, as indicated by the adoption of pre-Islamic regnal names such as Kayqubad and Kaykhusraw in the courts of Anatolia and India. However, we lack an understanding of why Persianate culture was appreciated by such elites, how it was transmitted, to what extent it was actually seen as distinctively ‘Persian’ and whether this ‘Persianness’ changed over time.

The research programme will encourage scholarly interaction through a major conference that will address such questions, along with considering the means of transmission of Persian culture and the role of migrant Iranians in this, the reason for its adoption and its appeal to non-Iranian elites and others, its interaction with other cultural traditions, whether Islamic, Hindu or Christian, in comparative perspective. Workshop participants would be encouraged to draw on evidence from a variety of disciplines – language, literature, art history and history – to provide a comparative perspective. By drawing together research from a wide variety of different disciplines, the workshops will shed light on aspects of the formation of Perso-Islamic civilisation and the influence of the pre-Islamic Iranian past.