May 2021 | BIPS Travel Grant

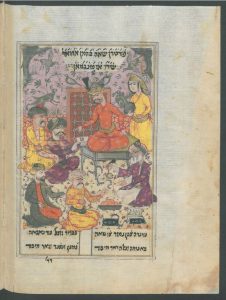

Folio 147v. from SPK Ms. Or. Quart. 1680 showing the start of the chapter entitled ‘Shah Bahman asking the astrologers about the Shiro’s wellbeing’

The BIPS travel grant received in May 2021 allowed me to undertake visits to the Staatsbibliotek in Berlin and to the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS) library in New York, to examine ‘in the flesh’ some manuscripts of Shahin-e Shirazi’s Ardashir Nameh, a part of which, the Shiro o Mahzad story, was the subject of my Masters’ research at Edinburgh University under Professor Jaakko Hameen-Anttila’s supervision.

Shahin is an undeservedly unknown Persian poet (fl. 1327-1359), whose output is preserved entirely in Judeo-Persian – i.e. New Persian written in Hebrew letters. He wrote three masnavi works, Musa Nameh (1327) based on Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy; Ardashir Nameh (1333), on the Book of Esther and Ezra, with the Shiro o Mahzad story as a sandwich filling; and Bereishit Nameh (1359), on Genesis.

Remarkably, none of Shahin’s works have been published in full, academic critical editions based on the best available manuscripts. Certain sections of Ardashir Nameh have been published in the very early 20th century in non-critical editions, based on a single manuscript. [1] In the last fifty years or so, various academic, myself included, have published certain chapters using more recently discovered manuscripts. [2]

However, the Shiro o Mahzad romantic story has been completely ignored by scholarship, other than the briefest of lip service; that is until now. My goal in my Masters was to study this romance in its context, meaning in the context of the work of which it is part, Ardashir Nameh, in the context of Shahin’s other works, and in the context of romance masnavi written by Shahin’s Muslim contemporaries such as Khwaju Kermani and Jalal Tabib, identifying and considering Shahin’s use or rejection of certain topoi, and seeing whether any evidence could be ascertained for interaction with his immediate contemporaries.

As part of this research, I sought to provide (myself and the readership) with critically edited versions of the chapters discussed, and these are in my Appendices B and C.

Whilst most manuscripts are nowadays available for study online, this is not the case for all manuscripts, and even where this is the case, the environments in which one might consult an online version (in my case, trains, planes and buses) are not ideal in terms of light and background noise. One also gets a better sense of the scribe’s investment in the manuscript from seeing the original, where one has a greater sensory experience that includes the quality of the paper, the coloured or golden lines around the text (some of my manuscripts are still in black and white microfiches).

Where words, lines or pages are blotchy, faded, or whited out in some way, I have found that being able to consult the original under strong quality light allows one to distinguish letters far more clearly than on a photocopy of a microfiche.

The Berlin manuscripts viewed were:

- Or. Quart. 1680. This is the oldest extant fragment (c. 1650) of Ardashir Nameh and will be the base manuscript for the critical edition I am preparing. It was donated in 1927 by Professor Ernst Herzfeld. This fragment is famous for its (Safavid) period illuminations, published by Moreen in 1985 in her ‘Judeo-Persian Illuminated Manuscripts’.

- Or. Oct. 3714. This is a much later copy, and it contains only the first half of Ardashir Nameh – ending after the Esther story. It was used by Blieske for her 1966 Ph.D. and its primary usefulness is that it preserves the chapter in praise of Abu Sa’id Bahadur Khan, to whom Shahin dedicated the work.

- 2085. This contains two chapters of Musa Nameh. I transcribed this manuscript whilst in Berlin, as I intend to work on Musa Nameh as part of my Ph.D.

The JTS manuscripts viewed were:

- 8270. This is the second oldest Ardashir Nameh fragment, but suffers from many of the folios being out of order, and from many lacunae. In aggregate it is significantly less complete than other large fragments. However, it is also famous for its illuminations, and has been used by past scholarship.

- 1443 (ENA 396): This was the manuscript viewed by Bacher in London, and which the JTS acquired from Elkan Nathan Adler. It dates from the 18th century, is perhaps the most complete fragment, just missing some folios at the start of the work.

- Two separate single folio manuscript fragments not available online.

David in the manuscripts room at the JTS library prior to commencing his work on their manuscripts. David was the first visitor after the JTS Library moved into its new facilities.

As a result of being able to work on the manuscripts themselves I was able to correct the transcription of many letters or words which were much clearer under library conditions, and this made a meaningful contribution to being able to complete the chapters that I included in Appendix C to my dissertation, and other chapters that I would have liked to include, but will now find a place in the critical edition I will publish.

Being in Berlin also allowed me to meet Professor Shervin Farridnejad, a scholar of Zoroastrianism, and Judeo-Persian, and whilst in New York I was able to hold a Zoom conversation with Dr. Vera Moreen of Philadelphia, who has published many articles and books over the last forty years in the field of Judeo-Persian literature.

The staff at the SPK and JTS were always very accommodating and helpful, and I would like to record my gratitude to them for their kind hospitality.

I would also like to take this opportunity to thank my Masters supervisor, Jaakko Hameen-Anttila and all the other UK academics in BIPS with whom I have interacted during my Masters.

Although I am off to do my Iranian Studies PhD in Hamburg, I shall be retaining links, as I hope to meet up with Professor Melville in Hamburg, where he is a permanent fellow of the Manuscript Cultures Centre.

David Gilinsky completed his Masters by research at the University of Edinburgh in August 2022, presenting a dissertation on: ‘The Shiro o Mahzad sub-plot in Shahin’s Judeo-Persian masnavi Ardashir Nameh (1333 CE) in its literary context’, and is commencing in autumn 2022 his PhD research at Hamburg University, supervised by Professor Shervin Farridnejad, and Professor Ronny Vollandt (LMU) on: ‘Shahin’s use of the Rishonim and their sources in his Judeo-Persian masnavis Musa Nameh (1327) and Ardashir Nameh (1333)’.

[1] S. Hakham, Sharh Shahin al Megillat Esther, H. Zukerman, Jerusalem, 1910; W. Bacher, ‘Le livre d’Ezra de Schahin’, REJ, 1908, pp. 249-280.

[2] D. Blieske, Ardashir Buch von Shahin-i Shirazi, Ph.D., Tubingen, 1966, pp. 45-84; A. Netzer (ed.), Montakhab Ash’ar Yahudiyan-e Iran, Tehran, 1973; Gilinsky, D., Introduction to Judaeo-Persian Literature concentrating on the Poetry of Shahin-i Shirazi including an original critical edition with English translation of Chapter 26 of Ardashir Nameh, BA Dissertation, Cambridge, 1992.