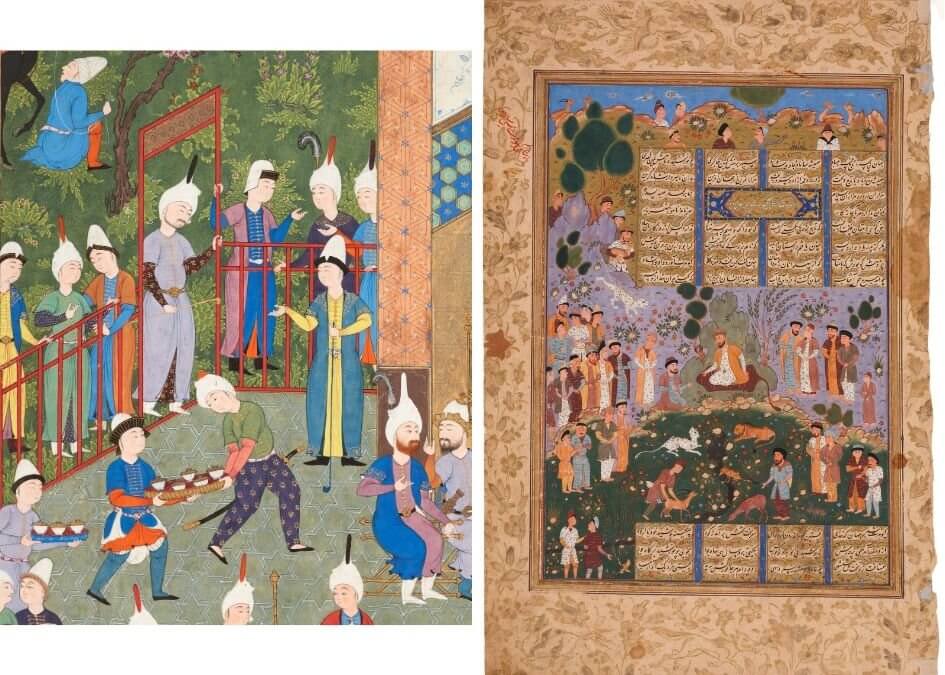

From the 13th to 17th centuries, the Persian literary masterpieces, like Shahnama by Firdowsi, Khamsah by Nizami and many others, were the sources of inspiration for painters of various schools and styles of Persian/Islamic visual arts. Persian miniature painting started to blossom under Ilkhanid patronage in the 13th century, when great focus was put on illuminating and illustrating the books. It reached its zenith under the patronage of the Timurid rulers in the 14th and 15th centuries, where the cities like Tabriz and Hirat were significant centres of manuscript production.

Tabriz remained active under the Safavids. The style was an explosion of highly decorative painting that can be seen in the early 16th century ambitious projects of Shah Tahmasp: Shahnama and Khamsah. However, by the mid-1540s, Shah Tahmasp stopped supporting art and artists. The artists who were then working in his court library travelled to neighbouring regions with still active libraries, namely Shiraz, Qazvin, Mashhad and Bukhara.

After the 16th century, Persian miniature painting diverged from manuscripts, mainly focusing on single-page portraits. The centre of this newly established style was Isfahan where the renowned Riza Abbasi created the best examples of the school.

While each school developed a unique set of stylist features, some general features continuing to exist as commonplace conventions in Persian miniature painting in almost all the schools – namely the bright colours, the even light and lack of shadow, three-quarter and round faces, simultaneous spaces and time, as well as non-perspective images.

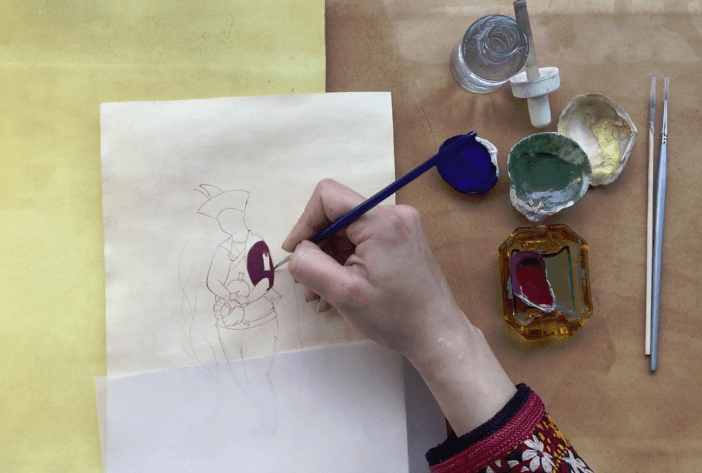

The process of creating a Persian miniature painting is twofold. The craftsmanship includes preparing the materials such as paper, brushes and colours. The painting process starts with sketching the composition and outlining the pencil lines in ink. What comes in follow is a summary of materials and techniques employed in the process of Persian miniature painting.

Paper- Looking at the illustrated and illuminated manuscripts, one may hardly find white papers. Almost all the papers used has been dyed or sprinkled with gold or silver. The reason, according to some painting treatises, is that the white background may deceptively affect the vision and weaken it in the long run.

Timurid and Safavid craftsmen explored the visual and aesthetic aspects of the papers. This yielded the innovation of the methods to prepare and decorate the paper such as marbling or dying, in order not only to create the pleasant experience for the audiences while reading or looking at the book but also inspiring and encouraging the artist while drawing.

To make an ideal paper, white papers are traditionally dyed with natural substances such as flowers, herbs and fruit juice by means of the soaking technique.

Colours- The colours used in Persian miniature paintings are mainly made with mineral, organic and herbal pigments and are mostly water based.

In the royal workshops, the pigments were from the stones (like lapis lazuli and malachite), earth (red ochre) and herbs (rose madder and madder root) and mixed with gum Arabic or egg yolk. According to the 13th century texts (Farukh-Namah, Yazdi and Bayan al-Ṣanaat, Teflisi), gum Arabic was added as a binder to those colours used on paper whereas yolk was employed for those used on wood.

Gold- Gold plays a significant role in the Persian miniature and Islamic illumination. Pure gold is made by pounding the gold among the layers of deerskin until it forms to a very thin leaf. The thin leaves will be ground with honey to make the shell gold.

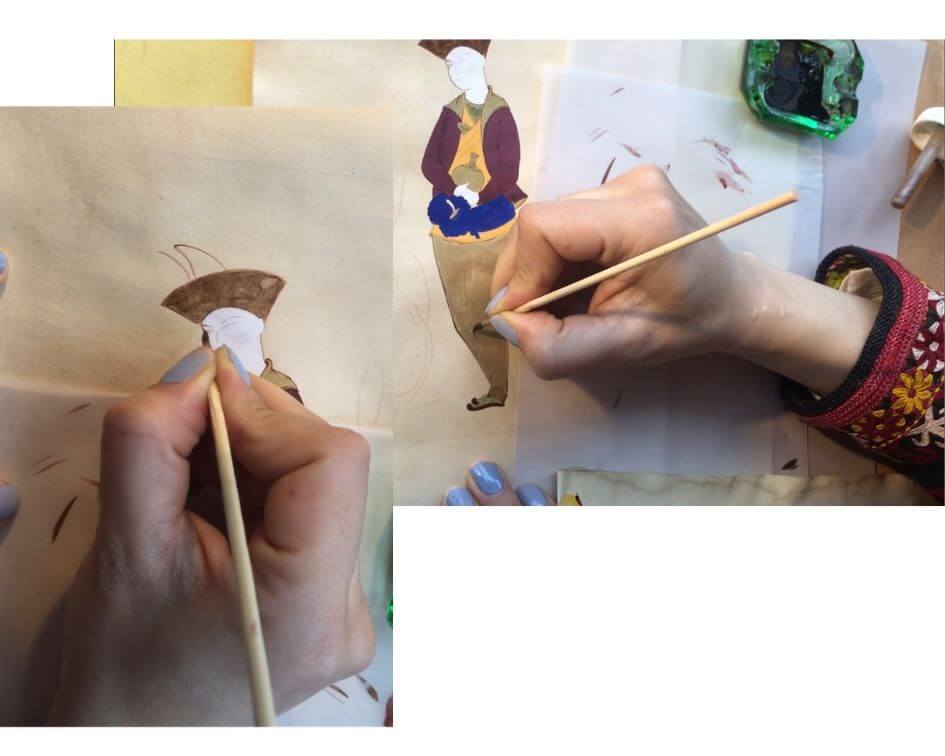

Painting- Colours will be applied after outlining the pencil lines in ink. Then every detail will be outlined again in another step. In fact, Outlining is one of the final steps, requiring the highest delicacy and skill to hold and move the finest brush.

Pardakht– One of the important final stages of painting is pardakht that is rendering the details. It is logical to say that it requires the highest level of technical artistry in Persian painting. This is indeed a tool in artists’ hand to construct and animate the nature, animals and human beings on paper, creating a decorative effect in the painting and bringing it to maturity. To put it another way, the technical mastery of making the details is a criterion defining the artistic level of artist and the value of his or her work. As Khawndmir (the 16th century writer) praising Bihzad’s mastery: “The most accomplished among all artists of the world, acknowledged master in his craft, Bihzad, unique in his era, in whose time Mani has been relegated to fable. Through his mastery the hair of his brush has given life to inanimate form. In precision of nature he is hair splitting…”

Once every step is done we need to create a framework, that is, a border including a series of lines with various thicknesses. Border defines a frame for the painting occasionally comprising decorative flowers, leaves and sprinkled gold.