May 2021 | BIPS Research Grant

The Department of Coins, Medals et Antiquities of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) holds a collection of over 1,000 coins struck by the Hellenistic kings of Bactria, descendants of the Greeks who arrived in the Central Asia following the conquests of Alexander the Great. The area over which these kings ruled consists today of parts of Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan. After a brief period of rule under the Seleucid Empire (from the end of the fourth to the middle of the third century BCE), the region became an independent kingdom under the control of kings who, for a little over a century, minted bronze, silver, and sometimes, gold coins, according to the existing systems of coinage in the Greek world.

In the BnF collection, gold coins are well-represented with 22 examples: eight of the Seleucid kings (Antiochus I Soter and Antiochus II Theos), ten of the Bactrians (Diodotus I or II, Euthydemus I, and Eucratides I) and four coins considered to be modern forgeries. Thanks to a research grant from the British Institute of Persian Studies a programme of metal analysis of these objects has been undertaken in partnership with the IRAMAT-CEB (UMR 7065, CNRS-Université d’Orléans) with the aim of determining the composition of minted gold in the Hellenistic Far East.

This programme, led by Simon Glenn of the Ashmolean Museum and the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents at the University of Oxford has been completed in collaboration with Julien Olivier of the BnF and Maryse Blet-Lemarquand of the CNRS.

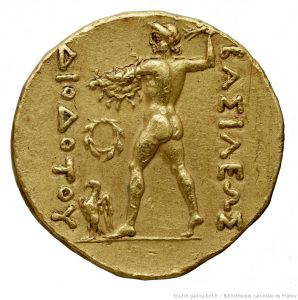

Stater of Diodotus I or II, 256/250–238/234 BCE. Gold, 8.56 g, 18mm. BnF, MMA, K 2825.

An outline of the project

Our best form of historical evidence for the Hellenistic period in this part of the world comes from coins. In many cases, coins are the only testimony of the existence of certain kings; we know of eight Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek rulers attested in written sources, while over 40 are known from their coins. The BnF holds one of the world’s most important collections of these coins, with 1,131 examples. Of these, the Eucratidion is the most famous, but another unique coin, an octadrachm of Euthydemus I, is important for its use in historical reconstructions of the period. The unique status of these coins, and lack of archaeological provenance, has sometimes called their authenticity into question, a concern exacerbated by the high value of all ancient gold coins and therefore their attraction for forgers.

Octadrachm of Euthydemus I, 223–200/195 BCE. Gold, 32.73 g, 31 mm. BnF, MMA, 1966.163.

Among the BnF’s collection of 22 coins, one spectacular gold example stands apart. Purchased in 1867 for the royal cabinet of Napoleon III the coin weighs 169.2 g and, as such, is the largest coin known to have been struck in Antiquity. It is unique. The king under whose authority the coin was made, Eucratides I, and who gives it its unique moniker, L’Eucratidion. Very little is known about the kingdoms over which Eucratides and his contemporaries ruled since the usual sources of evidence, familiar from the ancient classical Mediterranean world, are lacking. We have very few sources of literary history, almost no epigraphic evidence, and very few archaeological sites (with the famous exception of Aï Khanoum).

20 stater coin of Eucratides I, 165–145 BCE. Gold, 169.20 g, 58 mm. BnF, MMA, E 3605.

Analysis of the metal of the coins can be a way to address the concern of authenticity. This can be determined not only by comparing the results of the analysis with other ancient gold objects which have already been tested, but also by identifying trace elements in the alloy of the coins which may be indicative of a modern provenance. For example, a relatively high quantity of palladium may be characteristic of gold from South American mines, a source which was not available to the Bactrians and Indo-Greeks, and which would therefore suggest a much more recent date for the manufacture of the coin in question. More broadly, not only can the authenticity of coins be verified, but also questions of the likely source of metal interrogated. Does the particular signature of the gold used in the Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms share similarities with that of other Hellenistic gold coins, or does it seem to come from a separate local source?

The analysis at the IRAMAT-CEB

The programme of analysis was undertaken earlier this year and took a day to complete. The analysis took place at the IRAMAT-CEB laboratory with which the Department of Coins, Medals, and Antiquities has been collaborating for several decades, mainly in the field of economic and monetary practices.

Plasma mass spectrometer with sampling by laser ablation at the IRAMAT-CEB (©IRAMAT-CEB)

Plasma mass spectrometer with sampling by laser ablation at the IRAMAT-CEB (©IRAMAT-CEB)

The day began with a meticulous observation of each coin under a binocular lens. The objective of this inspection is to identify any traces of the process of manufacture – ancient or modern, this being one of the research questions of the project – of the coins (traces of re-engraving, or signs of the object having been cast when they would normally have been made by striking with a hammer). The metal of the coins themselves was also visually inspected, looking particularly for the presence of inclusions of platinum group elements. These grey-looking nodules are an indication of the use of alluvial gold, deposited in nuggets and flakes by the movement of water, and collected by gold panning.

The principal means of investigation, however, remains plasma mass spectrometry with sampling by laser ablation (LA-ICP-MS), a technique sometimes used in archaeometry laboratories. Performed on coins from the early 2000s, this method requires micro-sampling of material on each object, carried out using a laser. The ablation is extremely small, the crater produced not exceeding 80 micrometres in diameter (i.e., 0.0.8 mm) and therefore being invisible to the naked eye. Laser ablation has the significant advantage of allowing the calculation of the coin core composition since it goes beyond the surface layer of the object. This aspect of the analysis is extremely important for the study of alloys used in coins as very often the surface of the objects has been disturbed by metallurgical treatments and/or corrosion (although not in the case of non-alloyed gold), while the core retains the characteristics of the original alloy.

The first group of coins prepared for LA-ICP-MS analysis.

The first group of coins prepared for LA-ICP-MS analysis.

The calculation of the contents is carried out during the analytical session. The raw data recorded for the coins are calibrated with regard to the signal obtained for a series of standards (top left and right in the photograph above), whose exact composition is known. The final results are presented in the form of a spreadsheet listing the concentrations for each coin of the 20 different elements detected.

Why analyse gold coins?

The multitude of measured elements is related to the diversity of questions raised by the study of coin alloys, which can be divided into two categories: the study of the major and the minor elements. The analysis of the major elements, for gold coins, obviously gold, associated with silver and copper, leads to information on the metallurgical practices employed in the manufacture of the alloy. These elements make up almost all of the material analysed and their proportions are the consequence of standards laid down by the issuing authority or at least of the treatments applied during the making of the alloy (purification, or on the contrary, debasement). At the same time the study of minor elements (even trace elements present at a level of a few to a few thousand parts per million: 1 ppm = 1mg/kg) allows insight into aspects of the alloy which were not known or even detectable for ancient metallurgists. Some trace elements behave in a particular way. Platinum and palladium, for example, which have the advantage of never dissociating from gold, share its characteristics and therefore constitute a reliable tracer of the metal stock used. For further information on this subject, see M. Blet-Lemarquand, S. Nieto-Pelletier, Fl. Téreygeol, « ‘Tracer’ l’or monnayé : le comportement des éléments traces de l’or au cours des opérations de refonte et d’affinage. Application à la numismatique antique », BSFN, 4, 69e, 2014, p. 90-94. This methodology has already been used in several studies to characterise minted gold in the Eastern Mediterranean following the conquests of Alexander the Great. It appeared that the considerable gold coinage issued by Alexander and then during a large part of the Hellenistic period came, at least for the most part, from the treasures taken from the palaces of the Persian Achaemenid kings. See on this subject Fr. Duyrat, J. Olivier, « Deux politiques de l’or. Séleucides et Lagides au IIIe siècle avant J.-C. », Revue Numismatique 2010, p. 71–93. The relationship, or lack thereof, between this Hellenistic stock of metal and the gold of the kings of Bactria constitutes one of the main research questions of the programme undertaken here.

Results to come

Research takes time and the analysis carried out is currently being interpreted. These new data are compared with those obtained previously by the various means of numismatic investigation (study of the iconography, quantification of production, etc.), for example the recent contribution of S. Glenn on this subject (S. Glenn, Money and Power in Hellenistic Bactria, New York, 2020). Finally, these results will be compared with the other historical sources at our disposal, mainly archaeology and ancient texts, to assess the role and importance of the coins produced by the Graeco-Macedonian kings of Bactria between the middle of the third and the middle of the second century BCE. The results of this programme and the conclusions drawn from them were first presented at the XVI International Numismatic Congress held in Warsaw in September 2022 (S. Glenn, J. Olivier, M. Blet-Lemarquand, « Graeco-Bactrian gold: Metal analysis of the coins of the Bibliothèque nationale de France using LA-ICP-MS », XVI International Numismatic Congress, Auditorium Maximum – Hall A, 12 sept. 2022 à 09h40), then as the subject of an article which will be submitted to the Revue Numismatique for publication in 2023.

Further reading

Presentation of the Oxus-Indus project, A new typology of Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek coinage.

Olivier, « L’Eukratideion: un “monstre” numismatique », blogpost on L’Antiquité à la BnF, 01/08/2018.

J. Olivier, « L’Eukratideion: la plus lourde monnaie d’or de l’Antiquité | La #BnFDansMonSalon », online conference, 05/05/2020.

This blogpost is available in French at this link.